The daily life in the Leper Colony

The people admitted to Spinalonga mainly come from rural families with relatively low income and education levels. They live isolated, away from their families, struggling with a tormenting disease and barely surviving on the rough and arid island. Their way of life is determined by the regulatory decrees set by the Cretan State and subsequently by the Greek state. From the moment of their confinement, the patients are deprived of their political rights, lose their properties, and, in the case of being married, their marriages are annulled.

The lepers settle in the old settlement's lower levels, around the fortress's two gates, and form a unique social group with peculiar rules and values. During the first decades, they exclusively reside in the existing houses, which are old and lack even basic amenities. Later, in the 1930s, new buildings are constructed, significantly improving the living conditions.

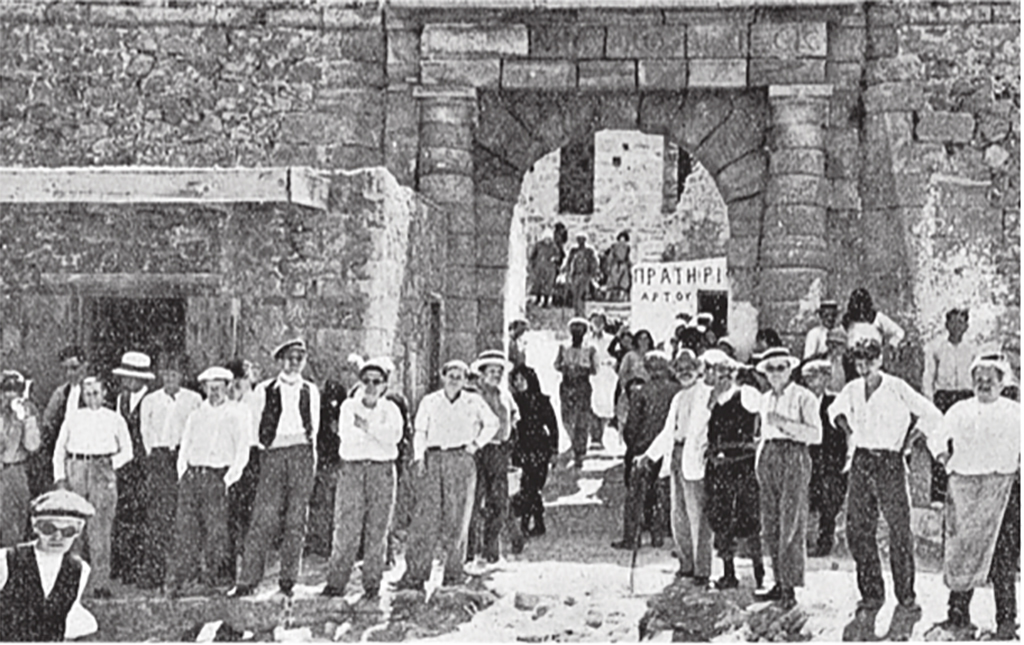

With the state allowance, they have economic self-sufficiency and have the opportunity to purchase basic food items. A small market is set up outside the main gate. Patients go there to buy various goods from local producers, and with the mediation of the guard, they pay with money which has been previously sterilized. Anything else they need, they order from the town of Agios Nikolaos or obtain from the grocery stores on the island. There are also cafes on the island operated by the leper patients themselves—those who can engage in vegetable cultivation and fishing.

Each leper patient lives in their own personal space and has their own household. It is said that there are mothers and spouses of the sick who follow them and settle with them on Spinalonga to take care of them. Notably, priests live with the lepers to perform Divine Liturgy and support them. Moreover, despite the state's prohibition of marriage among lepers, many get married and have healthy children who live on the island with their parents. After 1938, a branch for children is established at the Agia Barbara Contagious Diseases Hospital, and the "leper children" of Spinalonga are mandatorily transferred and settle there, where they are medically monitored until adulthood.

The sterilization furnace in the Garrison Building that housed the disinfection chamber. ©Ephorate of Antiquities of Lasithi

Donations cover the majority of the functional expenses of the Leper Colony. Also, many charities send packages with clothing and food to Spinalonga.

Patient care is deficient. Testimonies from various Greek and foreign doctors, researchers, and officials who visit the Leper Colony underline the absence of infrastructure and treatment. After 1948, when the new anti-leprosy treatment begins in Spinalonga, which has impressive results, the social rehabilitation of the patients begins, and most of them return to their hometowns.

The people with Hansen's disease eventually manage to leave the isolation; however, their social rehabilitation is nearly impossible due to the social stigma. Society has learned to reject them, and there is no place for them among the "healthy". In fact, the feelings of rejection that they experience after their release from Spinalonga and their transfer to the Anti-Leprosy Station are so intense that some patients nostalgically long for life on the island. At least there, they were protected from the society that rejected them as stigmatized.

From the perspective of the residents of the broader area, the operation of the Leper Colony displays some positive outcomes, as it provides economic relief to the poor Merampello region. The supply of food items and the care of patients constitute a considerable income for many households. In the last decade of the operation of the Leper Colony, the staff consists of an administrative Director, a doctor, an administrator, an accountant, five nurses, a disinfector man, a priest, eight boatmen, ten guards, ten female launderers, and ten women for the care of the helpless lepers. Several staff members reside across the Plaka settlement, which develops to support the Leper Colony.

Photo Gallery

Nursing staff of the Leper Colony outside the Disinfection Chamber. © Doxa Mavroid Archive

Snapshot from René Zuber and Roger Leenhardt's documentary "In Crete Without Gods" (1935). The openings made by the leper patients in the Venetian walls can be seen, as well as the market building next to the Main Gate,where merchants from the surrounding area sold their products to the patients.

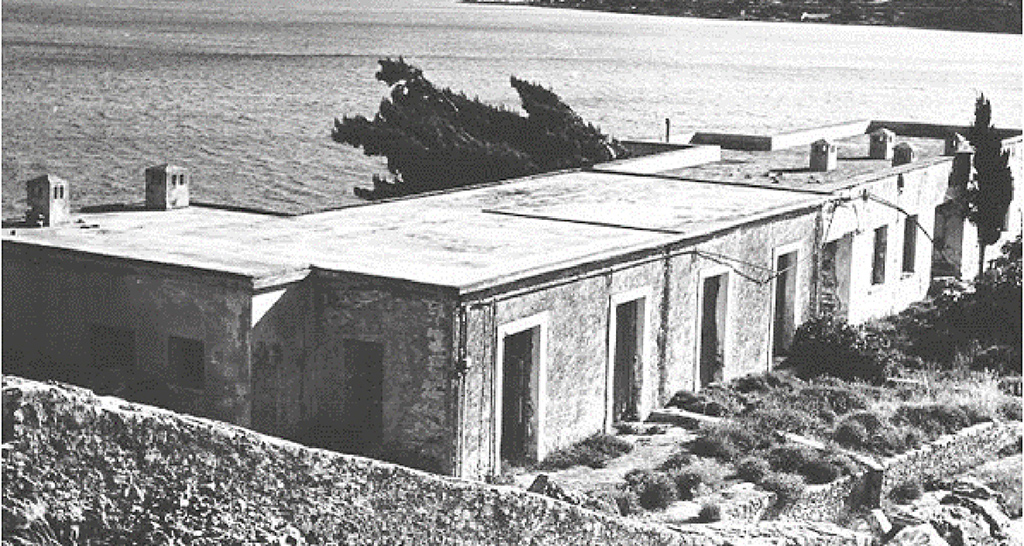

Buildings of the Leper Colony Hospital constructed in the 1930s on the Tiepolo bastion, today demolished. ©Ephorate of Antiquities of Lasithi

The Leper Colony cemetery. ©Ephorate of Antiquities of Lasithi